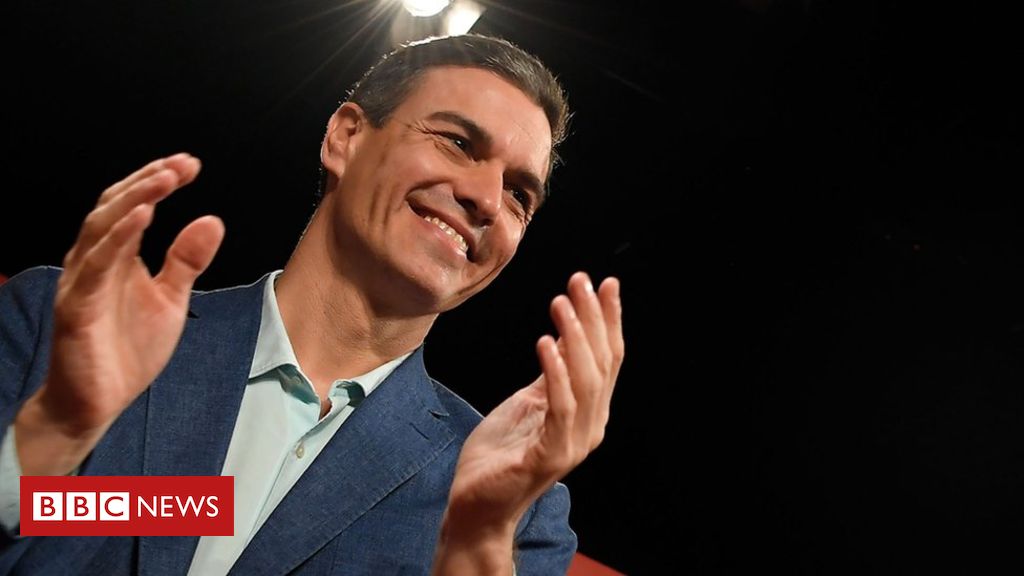

Less than a year ago, Pedro Sánchez was lagging in the polls as the leader of Spain’s opposition, bruised by two resounding electoral defeats.

Yet he goes into this Sunday’s general election as prime minister – and is widely tipped to secure the first victory for his Spanish Socialist Party (PSOE) since 2008.

“He has used his time in government to project an image of gravity and of being someone who is suited to the post of prime minister,” says Josep Lobera, a sociologist at Madrid’s Autonomous University (UAM) – who adds that being in government has boosted Mr Sánchez’s standing among leftist voters.

“Regardless of whether or not he’s actually managed the country effectively, he’s projected that image.”

Surprisingly popular

Mr Sánchez’s turnaround began in May of last year, when he launched a surprise no-confidence motion against prime minister Mariano Rajoy, whose Popular Party (PP) was besieged by corruption scandals.

Gathering support from the leftist Podemos and Catalan and Basque nationalists, the Socialist leader secured just enough votes to ensure the first successful no-confidence motion of the democratic era – making him prime minister in the process.

After lagging behind the PP in polls when in opposition, the PSOE shot ahead in the wake of Mr Sánchez’s arrival in office. Throughout his brief tenure, the PSOE has remained well ahead of the PP, the right-of-centre Ciudadanos, the leftist Podemos and the far-right Vox.

Mr Sánchez, 47, has taken a series of eye-catching measures which have appealed to his base, such as raising the minimum wage, appointing a female-dominated cabinet, and taking in the Aquarius migrant vessel after Italy had shunned it.

He has also begun the legal process to exhume the remains of the dictator Francisco Franco from his mausoleum and rebury them somewhere less divisive.

A battle for every change

By Mr Sánchez’s own admission, it has been difficult for him to take on more ambitious, structural reforms, with his party holding fewer than a quarter of seats in parliament. He told supporters at a campaign event that “it is true that in 10 months and with 84 seats [in Congress] we have not managed to change Spain, but we have managed to change its course”.

Plans to overhaul the education system, legalise euthanasia, change labour regulations and shake up national broadcaster RTVE have all been put on hold.

Yet Spain’s fragmented politics have worked to his advantage.

Ciudadanos, which once competed with the PSOE for the centre ground, has moved to the right. Podemos, the Socialists’ main rival on the left, has been riven by infighting, causing party leader Pablo Iglesias to admit recently that it “has disappointed a lot of people”.

Many former Podemos voters have subsequently turned to the PSOE.

Mr Sánchez’s recent resurrection adds to his reputation as a survivor. In 2016, in a previous stint as Socialist leader, he was ousted from the post following a bitter conflict within the party, triggered by two poor general election results and his refusal to end a national stalemate by facilitating the creation of a new, conservative government.

Defying the party’s old guard, he successfully ran in the 2017 primary, becoming Socialist leader for a second time – and paving the way for last year’s bid to become prime minister.

Catalonia and criticism

But while Mr Sánchez’s governing style has boosted his popularity on the left, it has drawn fierce criticism from the right. In particular, his approach to the Catalan territorial crisis, in which he has sought to lower tensions with the north-eastern region, has riled the opposition.

His administration has engaged with the pro-independence government, restored a bilateral working group, and allowed jailed Catalan politicians to be moved from Madrid to prisons in their home region.

Mr Sánchez has also held meetings with Catalan president Quim Torra.

Such moves prompted PP leader Pablo Casado to call the prime minister “the biggest villain in Spain’s democratic history”, casting him as an opportunist who was willing to negotiate the independence of Catalonia in exchange for the parliamentary support of nationalist parties.

Yet Mr Sánchez’s refusal to negotiate a binding independence referendum caused Catalan nationalist parties to withdraw their support for his 2019 budget, leading him to call this election.

Polls suggest that the PSOE will need the backing of Podemos and possibly other parties, in order form a new government. But this Sunday Mr Sánchez will not be the underdog – for a change.