The idea that France might restore Notre-Dame inside five years causes understandable concern among those who revere the 850-year-old cathedral.

Might the rush to rebuild result in an architectural travesty?

The short answer is that new technology has been applied to preserve similarly precious monuments in France – so much so that even the repairs gained “listed” status in time.

What kind of tech are we talking about?

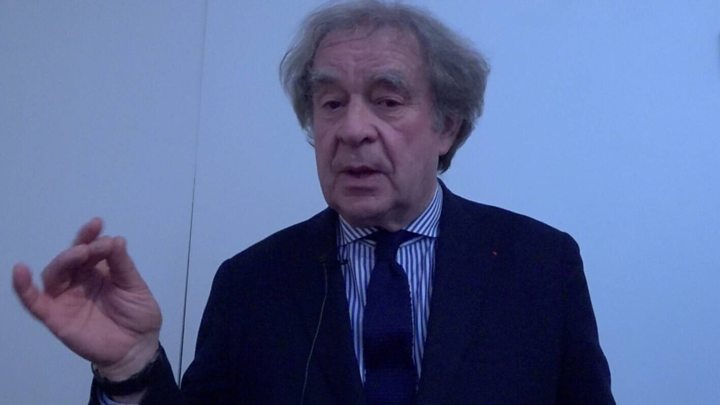

Jean-Michel Wilmotte knows a thing or two about cathedrals, having just built one himself.

He is the architect of the Russian Orthodox Cathedral that recently took its place in the Parisian cityscape on the Quai Branly.

Mr Wilmotte’s architectural practice also restored the Collège des Bernardins, a gothic religious building in the French capital just a century younger than Notre Dame.

To do so, it installed steel roof beams to support the custom-made new tiles.

Asked how the roof of Notre-Dame might be replaced, Mr Wilmotte suggests using a lighter structure of steel beams and titanium panels in place of the oak beams and lead sheeting that were lost.

Reims Cathedral, another French gothic masterpiece, burnt down during World War One in a disaster even greater in its magnitude than the one in Paris this week.

The architect who restored it, Henry Deneux, used a concrete frame that was innovative for its time and is now part of the building’s heritage.

Could Notre-Dame be repaired to medieval standards?

A 12th Century artisan turning up in 21st Century France could probably find the materials, and something like the tools, of his trade with the help of the country’s Historic Monuments firms, says Christiane Schmuckle Mollard, who worked on the restoration of Strasbourg’s gothic cathedral.

“Today’s artisan carpenters, roofers and stone masons,” she believes, “do an admirable job,” enjoying both recognition by major architects and the satisfaction that they are worthy of their ancestors.

“We could rebuild an identical structure for Notre-Dame because it has been perfectly documented and the materials exist,” says Denis Dessus, president of France’s National Council of the Order of Architects.

However, he thinks that the replacement roof is going to be a lighter, more flexible structure which will “allow this cathedral to live for another 10 centuries”.

“In any case, this will be an object of debate because both possibilities exist, to make it identical or optimise.”

How long should the work take?

French President Emmanuel Macron has called for it to be completed in five years, which would coincide with the 2024 Olympics in Paris.

Mr Wilmotte thinks that deadline is “very easy” and has a vision of using the River Seine to ship the materials needed for the job.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

“Wanting to tackle the problem head on is admirable,” says Mr Dessus, but he is concerned about moving too fast with such an old building.

Only after a full examination of the site can a timescale be envisaged, he says.

“To start work for the Olympic Games would mean going very, very fast,” he says.

Ms Schmuckle Mollard was “startled” to hear of President Macron’s plan and suggests past French governments would simply have promised to rebuild the cathedral as it was, “whatever the difficulties and however long the work”.

Mr Dessus reflects that “Gothic art is demanding both technically and artistically”.

The result, though, is the “timeless effect that grips every visitor”.